Summer School for Communication of Scientific Research

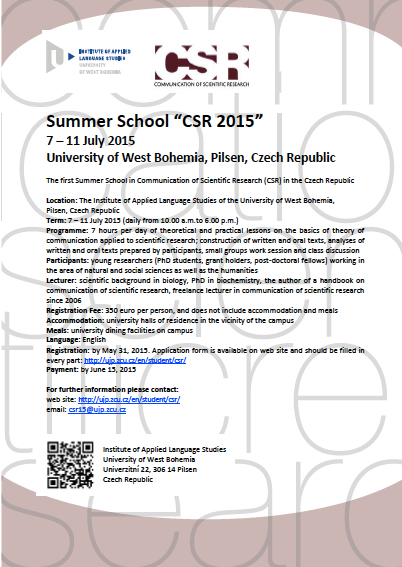

The first Summer School for Communication of Scientific Research (CSR) will be offered at the University of West Bohemia, in Pilsen, Czech Republic. [Click on the image above to download the flyer.]

Location: The Institute of Applied Language Studies of the University of West Bohemia

Term: 7 – 11 July 2015 (daily from 10.00 a.m.to 6.00 p.m.)

Programme: 7 hours per day of theoretical and practical lessons on the basics of theory of communication applied to scientific research; construction of written and oral texts, analyses of written and oral texts prepared by participants, small groups work session and class discussion

CSR: Communication of Scientific Research is different from the general communication of science, which implies the explanation of scientific matters to people who have not a scientific background (public and not specialized media). “CSR” is a discipline dedicated to the professionals of science, people who do know the matter, as they study, do research and work in this context. It does not depend on the disciplines, as it is not based on the contents of science, but on the tools used to communicate. “CSR” courses aim to start to fill a gap: a need for a more formal education on communication among young scientists.

Target audience: PhD students, post-doctoral fellows of different countries and disciplines (natural, social and human sciences)

Number of participants: maximum 20

Structure of the course: an intensive course of 5 days, with 7 hours per day, of theoretical and practical lessons dedicated to written and oral communication of scientific research.

Language: English

Application form due May 31, 2015

Registration Fee: 350 euro per person

Lecturer:

Maria Flora Mangano earned her PhD in biochemistry in Italy, at the University of Milan, in 1999; then she left the research laboratory to study science communication. In 2003 she started to teach communication through meetings and courses dedicated to trainees at scientific faculties of Italian universities. In 2014 she began a second PhD in humanities and intercultural studies at the University of Bergamo (Italy). Her website and the articles she publishes are attempting to start filling a gap: the need for more formal education of communication among scientists. It is a challenge for scientific disciplines, where so much research is done with such a little communication. She has published a handbook of communication of scientific research. It has been written both in Italian (1st ed. 2008; 2nd ed. 2013) and Spanish (2009). It is 100 pages long, and designed for science professionals: young scientists, including PhD students and postdoctoral fellows. It is offered to scientists as a tool to understand how to communicate their research, either written or oral, better. The handbook specifically deals with various forms including a scientific paper, poster, PhD thesis and scientific presentation. Maria Flora Mangano teaches communication of scientific research at Italian universities and organizes regular “schools.” Three courses dedicated to the communication of scientific research have already been held in Pilsen, at the University of West Bohemia, in 2014 and 2015. July 2015 will be the first summer school.

History and more details, including the complete Schedule are available. For further information about the course, please send an email.

Since 2007, she has been teaching Dialogue between Cultures and

Since 2007, she has been teaching Dialogue between Cultures and